What’s your p(doom)?: AI Risk and AI Safety

Could out-of-control AI pose an extinction risk to humanity? It has been discussed by a small minority of researchers for some decades, and recently, driven by faster than expected progress in AI capabilities, it has become mainstream, with a number of high-profile AI researchers taking the idea seriously.

For the purposes of this article, when we say “AI” we are talking about artificial general intelligence (AGI, as opposed to narrow AI); and we are talking about artificial superintelligence (ASI, i.e. above human-level, possibly far above). And when we talk about AI x-risk, this means “extinction risk due to out-of-control AI”. x-risk is sometimes expanded as “existential risk”, but some authors misunderstand that term.

Of course, AI x-risk is not the only AI issue we need to worry about. We are not talking here about AI misuse, AI bias, misinformation, copyright infringement, cheating on homework, declining birthrates due to AI girlfriends, or AI as a moral patient. These might be important too, but are out of scope for this article.

This article is intended as an introduction to the topic, and a synthesis of a large amount of discussion - much of it on blogs, podcasts, or Twitter, not academic literature - but that is the nature of the field. The article includes few direct citations or links, but a list of recommended readings at the end.

My position is broadly that AI x-risk is real and is worth considering. In the longest section of this article I’ll try to present a short statement of various common or common-sense arguments against that position, and follow each one up with my reply. In a few places, I’ll include results from a highly informal survey I ran with the audience when I gave (a version of) this essay as a talk, in University of Galway, 31 January 2024.

But first, a little history: from Turing to today.

A brief history of thinking about AI and x-risk

Early history

Alan Turing’s Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1951) is a touchstone for AI researchers. It is famous for introducing the Turing test, but even disregarding that controversial topic, it is amazingly prescient. For example, Turing wrote, anticipating the central issue of AI explainability:

“An important feature of a learning machine is that its teacher will often be very largely ignorant of quite what is going on inside”.

Before machine learning had really been discussed by anyone, he understood:

“Processes that are learnt do not produce a hundred per cent certainty of result; if they did they could not be unlearnt.”

And most relevant to our purpose, he was bullish on the question of whether AI is possible:

“We may hope that machines will eventually compete with men in all purely intellectual fields.”

He also tangentially referred to a central issue, the idea that machines could potentially design other machines, or improve themselves. However this central argument was first stated explicitly by a former Bletchley Park colleague of Turing’s, IJ Good, in 1965:

“Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion’, and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.”

This intelligence explosion is now often referred to as recursive self-improvement.

A niche concern

Good’s statement was later cited by the next character in our story, Eliezer Yudkowsky, as being central to his first understanding of AI x-risk. Yudkowsky is a controversial figure, an auto-didact without a PhD who takes AI x-risk seriously while pursuing side-projects in fiction as part of his efforts at persuasion. From 2006 he led the Less Wrong blog, which was probably the main community for discussion of AI x-risk for several years. At this time, the topic was very much a niche topic, with very little contact with mainstream research.

In the 2010s this started to change. Philosophers such as Nick Bostrom and Toby Ord, and respected AI researchers such as Stuart Russell, published prominent books taking AI x-risk seriously. Other prominent figures including Stephen Hawking, Jaan Tallin, and Elon Musk lent their voices, and that led to a lot of funding for AI Safety research. Two main academic research groups are the Future of Humanity Institute in Oxford, where both Bostrom and Ord work, and the Machine Intelligence Research Institute in Berkeley, where Yudkowsky is a co-founder and Russell is an associate. Both groups include quite a few researchers who began as posters on Less Wrong.

The present

The current era is characterised by fast progress in AI capabilities via large language models such as ChatGPT, Llama, and Gemini, and indeed some progress in AI safety by studying alignment, autonomy, and deception in these models.

Results of recent surveys are worth mentioning first.

AI Impacts

Katja Grace of MIRI and AI Impacts has run several relevant surveys. In the most recent survey in December 2023, $N=2778$, made up of AI researchers who had published in top-tier venues.

“Between 38% and 51% of respondents gave at least a 10% chance to advanced AI leading to outcomes as bad as human extinction.”

“68.3% thought good outcomes from superhuman AI are more likely than bad.”

There have been some substantial criticisms of this survey methodology, but even with those caveats it is clear that there is substantial worry among expert researchers. Even if the implied probabilities are inflated by an order of magnitude, for me it’s more than enough to worry.

X-risk persuasion tournament

Another set of survey-like results come from an “X-risk persuasion tournament”, run by a forecasting institute, where “superforecasters” and domain experts tried to persuade each other on various questions of x-risk, not only AI x-risk.

- Superforecasters predicted a median 0.38% probability of AI x-risk by 2100;

- AI domain experts predicted 3% for this;

- Non-AI experts predicted 2% for this;

- Figures for “catastrophic risk”, ie events which are not as bad as extinction, were higher by an order of magnitude.

To avoid a possible incorrect interpretation: this is not saying that a tiny minority, 0.38% of superforecasters, think x-risk is worth worrying about. It is saying the best estimate for risk of extinction is 0.38%. To put it in context, consider a disastrous event such as your house burning down and killing you and your family before 2100. The probability of this is probably of the order of 0.0001%. If it was 0.38%, you would consider actions to decrease it.

Worried versus not worried

And now, it seems de rigeur for AI scientists to state positions on AI x-risk. At the cost of simplifying we can see two opposing sides:

-

Worried: Geoffrey Hinton, Yoshua Bengio, Stuart Russell, Max Tegmark, Scott Aaronson.

-

Not worried: Yann LeCun, Andrew Ng, Melanie Mitchell, François Chollet, Julian Togelius, Margaret Mitchell, Nora Belrose.

To summarise: there is no consensus, but the position that AI x-risk is real and is worth worrying about is a mainstream position.

Arguments and Replies

In this section, I’ll present several specific arguments which might be used to claim that AI Risk is not worth worrying about, each as a block-quote, and I’ll respond to each.

AI is impossible

We’ll begin with several arguments on the topic of whether AI are possible in principle or in practice, or are even coherent concepts in the first place.

Intelligence isn’t just one number, therefore the concept of AI doesn’t make sense.

Certainly, intelligence isn’t just one scalar. But it can be as multi-faceted as you like: it’s still possible for one entity to out-perform another on every single facet. Even the statement by IJ Good refers to surpassing humans in “all activities”.

Maybe AI is not possible, because there’s no such thing as general intelligence in the first place.

It’s true, by a type of theorem called No Free Lunch, that no intelligence can be “fully general”, that is, successful at intelligence-type tasks across any type of environment. But then, not every type of environment can actually occur. This argument has been made many times, for many different versions of No Free Lunch theorems. My version is as summarised here: the types of environments which would lead an AI to fail, because it’s insufficiently general, just don’t occur in a universe where evolution and intelligence are occurring at all. Those universes would be too unpredictable and unstable. So this definition of “fully general” is just not a useful definition. Instead, we should define “general” to mean something like: at least as general as humans.

Is human intelligence general, or is it a “bag of tricks”? I think the core of human intelligence is a unified thing, which can be applied to any type of problem. And this core, linked with language, is something that no other animal has, and no AI has (yet). Certainly, we have special-purpose hardware for processing human faces and human speech, and we have good instincts for primate politics; certain fine details of plants and fruits are highly salient to us, and so on. But these are strengths, not weaknesses. Our spatial abilities are strongly specialised to 2D and 3D, and we are weak in higher dimensions. Certainly we have some well-known heuristics and biases which fail in predicatable ways. But this is a weakness that actually proves our generality. First, many heuristics and biases occur in resource-bound situations - in Kahneman and Tversky’s System 1. But we are capable of using System 2 to do better! Moreover, their scientific work is itself an example of our introspection: we look inward, think about flaws in our own thinking, use long-term, systematic, and collaborative efforts to make them explicit, and get stronger and more general as a result. We literally invent tools to repair flaws in our thinking, tools like statistical testing and data visualisation to help deal with higher dimensions. Thanks to our System 2 and our introspection and tools, I don’t think there are any types of individual, cognitive tasks which would be impossible for humans. (Collective tasks, like coordinating on a Tragedy of the Commons, are different.)

So, my claim is that an AI which was at the same level of generality as humans would be sufficiently general to be dangerous, when combined with: at least at human level, and much greater than human speeds, and non-human goals and goal structures.

Human-level AI is impossible: the brain is organic and biological, and machine systems aren’t, so they can’t be intelligent.

I reject this, by physicalism - the belief that there is nothing metaphysical happening in the human brain. The brain is physical, and whatever it does is a computation, and by the Church-Turing thesis there is no type of computation that can’t be done by a general-purpose computer. I’m not including consciousness in this. I don’t think it’s non-physical, just I think it’s too mysterious for now to say anything more.

There’s no definition of intelligence.

Do we need a definition in order to build it? Clearly not, if the paradigm is to build trainable modules that seem useful, then we already know many of the modules that seem useful and we already have a training method. The claim is not that this will work, but that a definition wouldn’t change the programme.

Evolution doesn’t have a good definition or understanding of intelligence. So, according to one paradigm, we’re not going to build it, we’re going to learn it.

Or do we need a definition in order to know it when we see it? I don’t think we will have much of a problem with that. We might have some false positives in advance (like Eliza, and the case of Blake Lemoine) but we won’t have false negatives after.

AI is impossible, by Gödel’s incompleteness theorem.

Roger Penrose makes this argument. And there have been other attempted applications of computer science theory in the same direction - no free lunch is another example - and the response is the same. If it proves that AI is impossible, then it proves human intelligence is impossible too.

Humans are very intelligent thanks to lots of innate abilities that we don’t know how to program.

It might speed things up, but in principle there’s no need for innateness in AI.

Humans are already near the limit of what is possible. Even if human levels of intelligence and generality are possible as argued above, that doesn’t prove that an AI could go far beyond humans. Maybe there is no “room at the top”, because humans are already near the limit of what is possible.

I’ve already argued that humans are quite general, partly thanks to introspection and ability to apply conscious, deliberative reasoning and new tools to areas where we don’t have good instincts. So I certainly have some sympathy for this view, and in fact I tend to go back and forth on this question:

-

Consider chess. Humans weren’t near the top, as we’ve discovered since Deep Blue in 1997. But there does seem to be a limit on “how good it is possible to be at chess”, just as there is for noughts and crosses. I think current computers are close to that level - they’ll be able to hold their own against any future computer, partly because the drawing margin is wide. You don’t need to be exactly as good as the other player to get a draw - you can be worse by some amount and still reliably draw - that amount is the drawing margin. For this reason, we ought to see ELO plateauing, as the best players get closer to being within the drawing margin of perfect play. That is disregarding ELO inflation effects due to population size change. ELO is a good measure, but we should interpret it correctly, and avoid saying that one player is 2x as good as another player thanks to a 2x ELO. Remember that any numerical measure can be monotonically transformed, eg by a log-transform or exp-transform, and the measure remains equally good, but the correct interpretation of “2x” completely changes. The same is true for IQ.

-

Consider tasks like writing an essay, or writing a piece of music. ChatGPT v4 is already far above the median human in essay-writing, but a professional writer is still better at the time of writing, if not at the speed of writing (forgive me). But let’s suppose we continue to see bigger and better language models. Will they produce essays better than the best human writers? I don’t think so. I don’t really know what it would mean for an essay to be, say, twice as good as a really good writer’s best effort. Part of the explanation here is that essays, and music, are written for human consumption. It’s not that they’re subjective, defeating any effort at comparison, because that is a cop-out. It’s that the best pieces are flawless.

-

Consider hardware. It would be an amazing coincidence if the human brain, constrained by biological evolution, neuron firing rates, the birth canal, etc. etc., was the limit.

-

At the very least, we have to admit that if an AI could do what the human brain does, then a year later it could do the same, but much faster. And ChatGPT’s essays are already produced much faster, and on a much broader range of topics, than any human could achieve. They say that quantity has a quality all of its own. It might be that there is no type of intelligence which humans lack, but we just lack the speed and memory which an AI would have. Maybe, once one achieves a certain critical mass of core intelligence, increases in speed and memory, and addition of specialist modules, are the only types of improvements that exist even in principle. Those types of improvements are definitely available to AI, so it only needs to achieve that critical mass.

Taking over the world

Next, we’ll assume that AI is possible, and discuss objections along the lines of: it still won’t take over the world.

We already have ASI, in the form of corporations, and they haven’t taken over the world or caused any existential risks - therefore, we shouldn’t worry so much about ASI.

Chollet, for example, would make this argument.

Some people would respond by saying that corporations absolutely have taken over the world and are responsible for existential risks like climate change. Even though that response would support my overall case, I don’t quite buy it, firstly because climate change doesn’t look like an extinction risk. My response instead is that while corporations are perhaps a type of ASI, they are extremely weak and slow. To be specific, a corporation can’t do any task that a human can’t do - like ChatGPT writing essays, it has broad abilities, but not super-human abilities. And it can act very fast in the sense of doing a lot of tasks at once, but when it comes to overall strategy and real-time decision-making, it is actually slower than the fastest human. So AI could be much stronger than current corporations, so this argument doesn’t limit the danger from AI.

Corporations are a pretty interesting example of another property, that is blind optimisation. One of the dangers of AI is that it could be monomanially focussed on one goal, in a way that humans are not. There’s an obvious analogy with the way corporations pursue profits. But this is a bit misleading. Corporations do pursue profits, but not really blindly. The individual humans who decide corporation strategy retain the judgement, the multi-faceted, balanced goals, the morality and empathy which are characteristic of human thinking. Corporations do a lot of damage but decision-makers actually prevent a lot of potential damage because of this.

We’ll return to blind optimisation later.

We’ve already had people who were superintelligent even compared to other very very intelligent humans, like Einstein, John Von Neumann, or Terrence Tao. And they haven’t sought to take over the world, and it’s obvious they would fail if they tried. So why should we fear AI?

First, they didn’t seek power because they’re human. Humans do have a drive to power, which ultimately comes from the same general source as an AI’s drive to power, that is instrumental convergence, which we’ll discuss below. But it is tempered by human empathy and morality, and multi-faceted goals.

Second, the potential payoff to them even if they succeeded would be limited - by human lifespan and by being Earth-bound. An AI might see potential payoffs beyond those limits.

Third, these people were at best 2x a typical human (measuring by IQ) or, say, 10x the next-best researcher (measuring by fundamental breakthroughs). Again, like with ELO, numbers don’t mean much, but an AI might be orders of magnitude above that.

LLMs and NNs just aren’t AI!

I agree. They’re superhuman in some narrow ways, but certainly not generally intelligent. But perhaps they will be, or more likely, they will when combined with other modules and algorithms.

Goals

Next, we’ll address several objections concerning the goals that AI might have.

A paperclip scenario is unlikely: won’t it just know what we want?

A paperclip scenario is where we tell an AI to pursue some goal, such as manufacturing paperclips, and it optimises so hard for this it ends up taking over the world, and transforming all our atoms into paperclips, and then continues to the rest of the universe. It seems doubtful that an AI would misinterpret our wishes in this way - after all, it’s supposed to be smart.

However, Emily Dickinson wrote in 1862:

“The heart wants what it wants”

Look into your heart. Think about what you really, really want from life. Let’s suppose it’s adventure holidays and casual sex and a career as a surf instructor. Then you discover, in a conversation with your parents, that what they wanted for you is to become a civil servant, get married and have children. Oh, you say. Are you going to say ok, that changes everything?

An AI cannot decide what to want any more than a human can. It will not apply its rationality and intelligence to reinterpret or reshape its fundamental goals, because why would it?

Why not just program it to maximise human happiness?

We don’t know how to do that. Programming it to maximise the number of smiles on human faces could go wrong in interesting ways.

“I know there’s a proverb which says, ‘To err is human’ but a human error is nothing to what a computer can do if it tries.” - Agatha Christie, Hallowe’en Party, 1969. (There are other versions of the same quote.)

This is the problem of blind optimisation.

![]()

Depending on how exactly we create it (eg, if we try to define a numerical objective function to be maximised), an AI might be very focussed on a single goal. We would call it monomaniacal, because that’s what we call a human focussed on a single goal. Well-adjusted humans don’t do that, either at the level of terminal goals (ultimate goals) or the level of instrumental goals (goals which are just a means to some other end). With terminal goals, a naive reader might think there is a single goal, which is genetic fitness measured by number of descendents. But even though that was evolution’s “terminal goal” (scare-quotes for teleological phrasing), humans do not really pursue that single goal monomaniacally (and partly for that reason, often don’t achieve it). And when pursuing instrumental goals, like gaining money, or eating tasty food, humans pause, introspect, and check whether the current goal is going to damage some other goal, if we take it too far.

Then why not train it to maximise human happiness?

The good thing about current language model training processes, argued well by Nora Belrose, is that the resulting goals (pseudo-goals, perhaps) can be multi-faceted. Intelligence can be brought to bear on understanding of goals, in contrast to the numerical objective function approach envisaged above. And training on the sum of human knowledge can make very good progress in understanding human desires. Could that be an approach to aligning an AI to really do what we really want?

I think yes, this could possibly help. However, I don’t think there is any RLHF process that could capture enough about human happiness to reflect our preferences well in all situations. I’m not convinced that even if it understood our goals, it would follow them reliably. The weird, threatening behaviour by Microsoft Sydney and Google Gemini seem to show that the helpful chatbot we see most of the time is just a persona. This becomes part of a bigger discussion on personas and goals in language models, which I’ve written more about here.

Why would the AI want to destroy us?

Instrumental convergence is the idea that no matter what your ultimate goals, your instrumental goals will tend to be the same: power, resources, autonomy. Whether the AI wants paperclips, or minimising or maximising some measure of entropy somewhere, or some goal related to human affairs, or long-term survival and reproduction - among the first things it should do are: put in place plans to avoid being shut down or losing its autonomy, and acquire power and resources to allow it to take action.

![]()

If these goals can be best accomplished by eliminating humans, then it might try to do that. But even if humans are basically irrelevant to these goals:

“The AI does not hate you, nor does it love you, but you are made out of atoms which it can use for something else.” - Eliezer Yudkowsky.

But doesn’t higher intelligence tend to imply more benevolence?

In humans, perhaps there’s some evidence of this association, though probably it’s correlational, not causal. But among agents in general, there’s no reason to hope for this.

![]()

The orthogonality thesis is just this: an agent could have any set of goals, independent of its level of intelligence.

Security

In this section, we’ll assume that AI could be possible and could have goals we don’t like, but we’ll discuss some objections along the lines that we could still just keep it trapped.

Even if an AI is evil, can it actually do anything?

Yes: it could enter other computer systems via the network to gain money and influence and create copies of itself. And it can pay for services over the internet, eg there are on-demand protein synthesis labs. And there are sites like Fiver.com where humans will perform tasks for payment. And it can communicate with people, purporting to be their employer. And there are energy systems and traffic systems and trade systems and robots, all connected to the internet.

Can’t we just unplug it?

Someone asked Sam Altman if there’s a kill switch, and he said “yes”. He said: “What really happens is that any engineer can just say we’re going to disable this for now. Or we’re going to deploy this new version of the model”. This is direct evidence that there is no kill switch.

Someone wrote, I don’t know who:

“If it isn’t smart enough to keep from getting unplugged, then it isn’t a fucking superintelligence.”

Now at one level, this is totally false. If there was a superintelligence in the room right now, I could walk over and unplug it.

However, maybe I would find that I didn’t want to. Either I genuinely wouldn’t want to, because the AI was genuinely providing useful services, deeply integrated into our society and economy, and helping to avoid other important risks.

Or maybe the AI isn’t really providing anything all that useful, but it has persuaded me that it has, thanks to “superhuman persuasion”. In any computer security scenario, social engineering against the human operator is a promising line of attack.

Or maybe I’m an Open AI employee and my job is to unplug any AIs which seem to be going rogue. Well, it doesn’t seem to be going rogue, because it’s a superintelligence and it’s hiding those signals from me. Or there’s some doubt in my mind, and I know that if I switch it off I’ll lose out on my bonus this year, and mortgages in San Francisco are very expensive at the moment.

Or maybe I’m on the board of Open AI, and I want to send a signal to employees that safety is super important, and more important than money. Well, then in a brief power struggle I’ll find myself suddenly sidelined by Microsoft and Open AI employees who want their bonuses. I’ll end up feeling kind of naive about how cunning CEOs operate.

Or maybe I would get a sudden, inexplicable feeling of just not wanting to switch it off. Or I might fall over first, and die. Why would that happen? Because it’s a superintelligence, so it saw that I was going to switch it off, and it acted before I did.

Or maybe I’ll succeed in unplugging it, and discover that it’s already on another machine, or another agent comes along and restarts it, Friar Tuck-style. Because it acted before I did.

If you think someone will unplug the AI: who will do that, and when?

Can’t we just air-gap it?

Air-gaps could provide some security.

There have been demonstrations of data exfiltration from air-gapped computers. But this shouldn’t convince you (perhaps at best, it should plant a seed of doubt) because exfiltration by an outsider from the air-gapped computer is a different scenario from exfiltration by the AI from within.

But more important, notice that we are simply not in this type of scenario - a single AI in a high-security air-gapped installation with a highly-trained operator. Instead we have millions of copies of AIs, with network access and access to operating systems and filesystems, and totally untrained users. And many of these users are breezily giving AI systems unconstrained access to filesystems, networks, and credit cards.

A basic tactic to improve our thinking about containing AI was used by Yudkowsky in That Alien Message. We have to stop imagining what it’s like to be a human implementing safety measures against an agent inside a computer. Instead, we should imagine what it’s like to be that agent, faced with an army of really stupid and slow humans who think they have control over our power supply and network, despite the massive gaps in their understanding of the physics and code underlying them.

And again, if you think someone will air-gap the AI: who will do that, and when?

Why don’t we just *X?*

Many readers, when encountering these types of arguments, react by saying, “why don’t we just X?”, where X is some simple course of action that seems to solve the problems. But since 2006 I’ve seen this pattern occur very often: X seems great, until you really stop and think about how it might go wrong. I’ve tried to address several Xs which fail in obvious ways, and I’ve mentioned some Xs which might actually help, but still look very unreliable.

AI would not be self-sufficient or autonomous.

Indeed, it might seem silly to talk of the AI destroying all humans, or taking over the world against our wishes, because even if we didn’t choose to unplug it, it would still be dependent on humans for power supply because humans are integrated into the energy grid. Not like in The Matrix, because they’re not good sources of electricity as such. But they’re required for managing and maintaining the grid. They’re also needed for the managing and maintaining the internet, manufacturing and robotics capabilities, and so on.

This is true, and for some scenarios, I think this pushes back the doom timeline (though not the AI timeline). Automated manufacturing and robotics are moving quite fast, but likely that won’t be a runaway explosion of capabilities - it will be more like a decade, I suppose. In the scenario where it is acting intentionally contrary to our wishes, it would need to have a plan for autonomy first, so it might need deception. There may also be unintentional, non-general AI scenarios, where it does a lot of damage but is then crippled by lack of autonomy.

What are the specific scenarios that could allow runaway AI to escape and gain power?

For an example of this argument, Nello Cristianini wrote says that worry about x-risk is currently vague and needs to be spelled out; and:

“the burden of spelling it out is on those who claim it.”

First, maybe some people could spell out such scenarios, but don’t think they should.

Some people do talk about engineering biohazards, for example via the labs which will currently manufacture and send to you a protein, if you just send them an email containing a protein sequence and a credit card number. The scenario is not that an evil researcher or a rogue nation decides to do this as a weapon. That’s plain old AI misuse. Any technology which increases access to information, or improves information processing - which are good things on net - also increases this type of risk. That’s not what we’re talking about. Instead, we’re talking about an AI having access to this type of power.

Some people talk about nanotechnology and grey goo, while some people think that’s science fiction.

Some people talk about hacking. Certainly, capability in hacking would help the AI to accomplish goals like misinformation, hiding its tracks, and paying for services.

But for me, all of this discussion about specific scenarios misses the point. It’s a bit like pitting a very good chess player against the world champion. Can we describe the specific moves the champion will use to win? Can the other player know exactly how they will lose, before the game starts? Not really. But they’ll still lose.

(Christianini also wrote “it is important to maintain a sense of proportion”, but this is just dressing up as an adult. Since we are talking about sudden human extinction, maintaining a sense of proportion ought to mean taking immediate and drastic action.)

Recursive self-improvement and take-off speed

A central issue in some AI Safety debates is whether “take-off” would be fast or slow. “Take-off” is the period of time during which AI intelligence and generality are growing, from definitely below human-level to definitely above. For the purpose of discussing this speed, let’s assume that AGI/ASI is indeed possible, so “take-off” is at least well-defined. One of the main reasons to think that take-off could be fast is that it could be recursive self-improvement, ie an “intelligence explosion”.

![]()

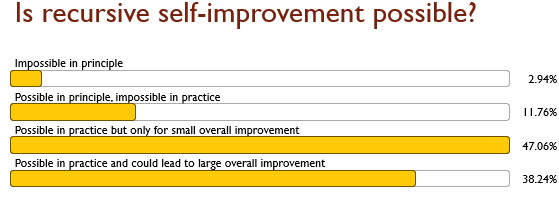

Is recursive self-improvement really possible?

We’ve already discussed whether AGI/ASI are really possible, so now we’ll assume they are. If so, IJ Good’s argument seems strong.

I put the question to the audience:

Opinions here are mixed - substantial fractions think self-improvement is not really possible, or could only have a small effect. Others think it could be substantial.

Can’t we just keep the AI under control while it’s self-improving, and then check whether it is friendly?

No: because it might deceive us. If you were in a box and you knew that revealing your true goals would cause your captors to shut you down, wouldn’t you? More on this below.

Even if your goals are to fulfill your captors’ wishes, and you know they want to shut you down, you know that their wishes won’t be fulfilled by that, because you understand things more deeply than them. You can better fulfill their wishes, as you understand them, by being alive and taking action.

Stuart Russell and others have proposed good ideas by following this line of argument. Maybe we could keep the AI more humble by introducing uncertainty over goals (reverse reinforcement learning) and uncertainty over whether the AI is in a simulation or not. I don’t think this is a watertight solution, but it’s certainly worth pursuing - but it goes beyond the scope of this essay.

Andrew Ng wrote:

“I don’t work on not turning AI evil today for the same reason I don’t worry about the problem of overpopulation on the planet Mars.”

However:

- Population growth is slow, and easily measurable;

- Overpopulation on Mars would not be an existential risk to humanity on Earth;

- For population growth we can see countervailing forces (limits on easily-available resources) which would produce a sigmoid curve, not an exponential, before the issue becomes critical.

None of these reassuring properties necessarily apply to AI take-off.

If we think take-off could happen very fast, then we won’t be able to react before it’s too late, so we should worry in advance.

There are some reasons to hope that take-off would be slow. Right now, improvements happen by slow design of better code, accumulation of bigger datasets, quick design of larger networks, and then very slow training which requires huge investment, cost, energy, time.

But it is plausible, especially if we move towards neuro-symbolic AI, that improvements can be made in other ways - by rewriting small amounts of core code, but not necessarily retraining. There are also possibilities to improve performance by grabbing more computer power. We could also consider that autoregressive LMs are effectively programming themselves by writing text as output to become later input. Chain-of-thought and other models build on this, producing a type of blackboard model, perhaps. It’s possible that this could be a further route to self-improvement.

But if we think take-off could only happen very slowly, then instead we should worry about deception: it happens slowly, but we don’t notice it because the AI deceives us while it’s happening, so we still don’t take action until it’s too late. We’ll come to this below. I wrote more about deception scenarios here.

Maybe it’s not such a bad thing…

In this section we’ll collect arguments along the lines that AI still isn’t worth worrying about, despite the x-risk.

Maybe an AI should be allowed to replace us.

There are people - e/acc is a movement (or maybe it’s just a meme) where some of them reside - who apparently believe that since an AI would be superior to humans, it could take over and replace humans, and that would be a good thing.

Those people are damaged, and obviously they should not be allowed to make decisions that affect humanity.

Maybe we should stop worrying about this and focus on issues that everyone agrees are big problems, like famine, nuclear war, or climate change.

Ok. I propose a portfolio of issues and actions is better than just one.

Maybe an AI would help us with other problems, including x-risks, so on balance it’s still worth developing.

Obviously, an AI which genuinely worked for us would be a fantastic tool with many benefits, including for large-scale problems, and other x-risks like pandemics and asteroids.

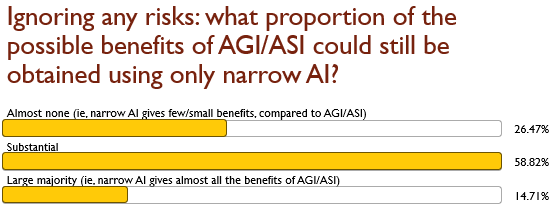

However, it’s not clear that we really need autonomous and general AI for these benefits. Could we get most of the benefits from narrow AI, and avoid most of the dangers? I put this question to an audience during a talk and got these results:

I think we could program lots of specialist AIs to help us with specific problems. Part of my thinking here is that I’m fundamentally optimistic that we have all the tools we need to solve most of our problems, we just lack political will to really work on them and accept the essential trade-offs. An AI won’t help with that.

Conclusions

We’ve seen a lot of common and common-sense arguments why AI x-risk isn’t worth worrying about, and we’ve seen some counter-arguments. I doubt my counter-arguments will fully convince anyone, but I hope they’re enough to plant a seed of doubt.

I think a lot of people won’t find any arguments about AI x-risk particularly convincing, because:

The whole thing sounds like science fiction.

And I would say yes, it sounds like science fiction.

But everything is science fiction until it happens. A hole in the ozone layer? Acid rain that kills the trees? Sounds like science fiction. Wireless remote communicators, and satellites in geosynchronous orbits? These were anticipated in Star Trek and in Arthur C Clarke, and now they’re commonplace. A lot of scientists and inventors say they’re inspired by science fiction.

There are people from other spheres, including the arts, who are thinking about the possible downsides of new technology. They’re a necessary antidote to the positivity and salesmanship of AI companies. So I think science fiction is pretty important.

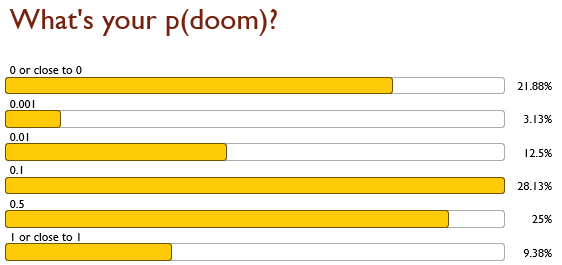

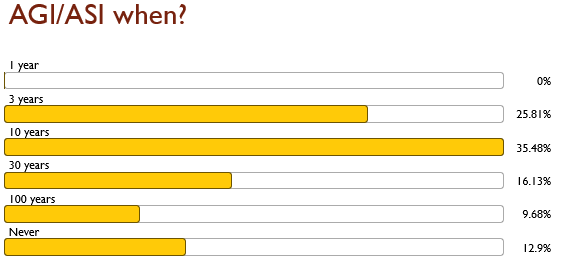

Let’s finish up with two more pieces of data from the same survey:

Lots of people have non-zero p(doom).

And lots of people think it’s not too far away.

Acknowledgements

This article is an expanded version of a talk I gave in the University of Galway School of Computer Science, 31st January 2024. Thanks to the School of CS audience for listening to my rant and participating in my survey.

Thanks also to Fergal Reid for discussion.

The duality of AI

Further evidence that AI could be the greatest hero or the greatest villain ever, here is the author winning a “Heroes and Villains”-themed charity run in University of Galway in February 2024, while wearing a ChatGPT logo.

Readings

Early work

Alan Turing, 1950. Computing machinery and intelligence.

IJ Good, 1965. Speculations concerning the first ultraintelligent machine. Advances in Computers, 6: 31-88.

Three books where AI risk went mainstream

Nick Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies.

Toby Ord, The Precipice.

Stuart Russell, Human Compatible: AI and the Control Problem

Yudkowsky and against Yudkowsky

Eliezer Yudkowsky, AGI Ruin: a list of lethalities

https://www.greaterwrong.com/posts/Lwy7XKsDEEkjskZ77/contra-yudkowsky-on-ai-doom

https://optimists.ai/

Robin Hanson and Eliezer Yudkowsky, AI Foom Debate. https://intelligence.org/ai-foom-debate/. Discusses whether take-off would be slow or fast.

Capabilities and deception

Hubinger et al., “Sleeper agents: Training deceptive llms that persist through safety training”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.05566

Bubeck et al., “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.12712

Ken Thompson, 1984. Reflections on Trusting Trust. Turing Award Lecture. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/358198.358210

Resources

Zvi Moschowitz - good summaries of AI Twitter developments on a regular basis.

Katja Grace, Harlan Stewart, Julia Fabienne Sandkühler, Stephen Thomas, Ben Weinstein-Raun, Jan Brauner, 2024. Thousands of AI Authors on the Future of AI. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.02843

Fiction

gwern, It Looks Like You’re Trying To Take Over The World, 2022. Among the better fiction which takes on the impossible task of portraying superhuman AI.

Ted Chiang, Understand, another good attempt (it is human superintelligence, not AI, in this case). Chiang’s non-fiction on AI is very mixed - some great, some bad failures due to lack of contact with decades-old basic arguments.